More Information

Submitted: 10 March 2020 | Approved: 06 April 2020 | Published: 07 April 2020

How to cite this article: Breijo-Márquez FR. PR and QT intervals short on the same electrocardiogram. Arch Vas Med. 2020; 4: 001-004.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.avm.1001010

Copyright License: © 2020 Breijo-Márquez FR. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Hemoglobinuria; Breijo’s electrocardiographic model; PR-interval; QT-interva; Arrhythmia. Cardiac Arrest; Sudden cardiac death

PR and QT intervals short on the same electrocardiogram

Francisco R Breijo-Márquez*

Professor of Clinical & Experimental Cardiology. MD. PhD. East Boston Hospital. School of Medicine, 02136. Tremont ST. Boston Massachusetts. USA

*Address for Correspondence: Francisco R Breijo-Márquez, Professor of Clinical & Experimental Cardiology. MD. PhD., East Boston Hospital. School of Medicine, 02136. Tremont ST. Boston Massachusetts. USA, Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

In 2007, Professor Breijo-Márquez described an electrocardiographic pattern, consisting of the presence of a short PR interval (or PQ) together with a short QT interval in the same individual. It was published with the headline “Decrease in cardiac electrical systole” in International Journal of Cardiology (IJC) [1].

Since then until the present, this electrocardiographic model is increasingly studied and diagnosed by several cardiologists, both in its isolated form and as forming part of other different cardiac alterations. As is well known, the PR interval in the ECG tracing represents the distance from the beginning of atrial depolarization to the beginning of ventricular depolarization. Standardized values, considered as in the normal ranges, oscillate from 0.120 milliseconds to 0.200 milliseconds (below the digit of 0.120 milliseconds is considered as “short”; above the value of 0.200 milliseconds is considered as an “atrioventricular block”) [2].

In the same way, it is also well known that, the QT interval includes both ventricular depolarization (QRS complex) and ventricular repolarization (T wave); it covers from the onset of the Q wave (if any) or onset of the R wave to the end of the descending branch of the T wave, when this branch reaches the isoelectric line of the electrocardiographic tracing (ECG).

However, at present, there are still many discrepancies about what should be the values considered as a standard when it is about the QT interval. The standard values in the length of this interval are not precisely uniform for all authors – depending possibly on the interests of each one of them. For most authors, including us, the values oscillate from 0.360 milliseconds to 0.450 milliseconds (for some authors in women they would be in ranges up to 0.460 milliseconds).

The shortening of the PR interval below 0.120 milliseconds, makes the myocardium more unstable and more likely to cause cardiac electrical disturbances, leading to arrhythmias that can prove exceptionally threatening to life; the most frequent arrhythmias are tachyarrhythmias in its different types and etiologies [2]. The short QT interval (equal to or less than 0.350 milliseconds) seems to be a rare form of channelopathy with a high risk of sudden cardiac death, but it is not yet well and completely defined, and information on long-term follow-up is still very scarce [3]. A short QT interval is the main component, but due to a strange relationship between the QT interval and the RR interval in patients with a short QT interval, the shortened QT interval in such patients is often only apparent at a heart frequency close to 60 bpm. Since routine ECGs are often taken at a faster cardiac rate than this, many patients with cardiac electrical involvement may be overlooked [3].

AThus, most diagnoses are based on the clinical presentation the patient’s own with a family member who has died suddenly, and the latter is also complicated to prove. The treatment of choice is an implantable defibrillator [4-6].

The standard values for us – and the majority of authors – are consequently:

PR Interval: From 0.120 milliseconds up to 0.200 milliseconds.

Corrected QT interval: From 0.360 milliseconds up to 0.450 milliseconds (in healthy women it is considered normal up to 0.460 milliseconds) [3].

We speak of corrected QT interval because a calculation must be made between the value of the obtained QT interval and the value of the RR interval measured beforehand to the obtained QT interval. Whenever an alteration occurs in the heart’s electrical system – in this case, in the length of the different intervals in the ECG tracing – the heart becomes much more vulnerable, and electrical instability is manifest, causing numerous and severe types of cardiac arrhythmias, some of them could be fatal.

In this case, a decrease of the PR interval together with a shortening of the QT interval in the same individual, the previously commented vulnerability and the electrical instability could be much higher and even deadly. Moreover, however, when the patient who suffers this type of alteration is in basal and asymptomatic conditions, the electrocardiographic tracing can be considered as “within normality,” and go overlooked and thereby misdiagnosed, when in reality both intervals are short and, therefore, the patient is highly susceptible to suffering severe alterations of the cardiac electrical system, including sudden cardiac death.

The typical patient suffering from this electrocardiographic model is a woman, in the third decade of her life, with multiple attendances to the emergency services, with mild symptoms of palpitations, profuse sweating (which usually disappears upon arrival at the hospital), somewhat agitated, with vital signs within average values, and with analytical values also within ordinary, except for the values of lithium in blood that are always below the thresholds. The symptoms reported by the patient are mostly at night, waking the patient.

In almost all cases, the electrocardiographic tracing is usually considered normal (although in all traces the PR and QTc intervals are short). They are discharged from hospital with the prescription of benzodiazepines and with a request for psychiatric evaluation. If we examine these patients in-depth, we can find that more than 90% of them had convulsive seizures in childhood without any electroencephalographic substrate and empirically treated with anticonvulsants. The reported symptoms are repetitive, and attendance at emergency services is constant, with identical results of hospital discharge.

Until the time may come when the patient no longer comes on her own since the access has been very severe and either she is in a cardiac arrest or has suffered a sudden cardiac death. In closing, we can state that not all patients with this sort of symptomatology have a psycho-somatic basis, but instead they have an organic substrate in their cardiac electrical system and, therefore, their heart is much more vulnerable and unstable than in healthy people. Thence, the study of every one of the parameters to be assessed must be thoroughly studied. In this way, we can avoid much greater evils, such as cardiac arrest and even sudden cardiac death aforesaid.

As a “closing” we can affirm that the electrocardiographic model with short PR and QTc intervals exist, that it can produce high cardiac electrical instabilities and that, therefore, it must always be evaluated in detail in all electrocardiographic tracing and never be discharged from the hospital without being sure of its presence. It is noteworthy that the author and his team have seen and diagnosed this variety of arrhythmia both in isolation and forming part of other cardiac disorders such as Wellens Pattern [7] (Figures 1,2), Wolf-Parkinson-White [8] (Figures 3,4) and others [9].

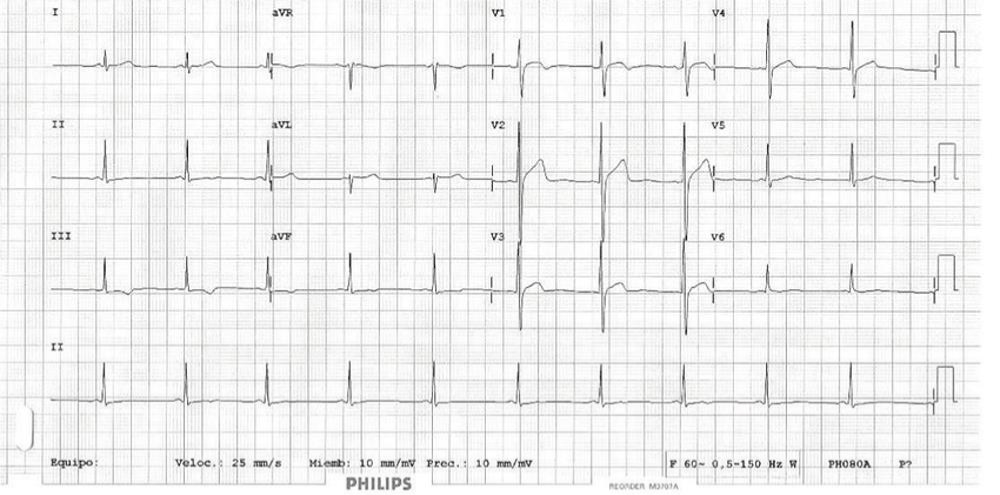

Figure 1: This figure was the first electrocardiographic tracing that the author studied and corresponded to a 36-year-old male with the symptomatology mentioned in the text [1].

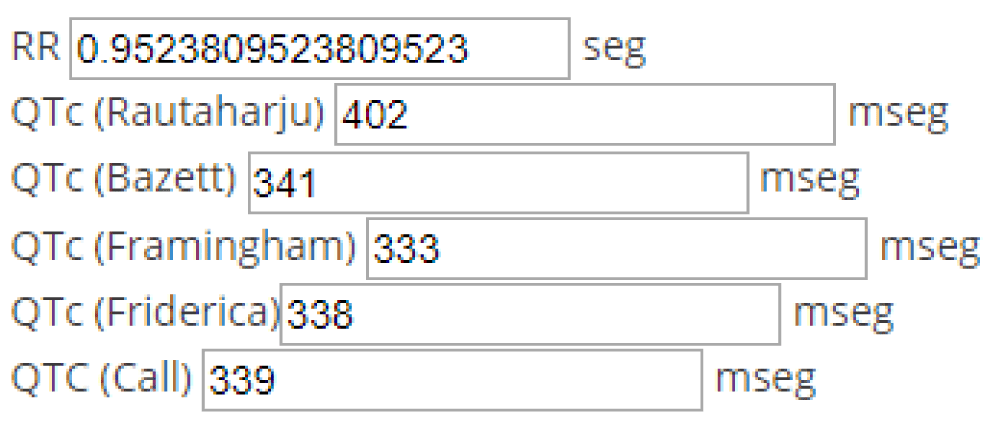

Figure 2: Values obtained utilizing the most commonly used formulas relating the measured value of the QT interval and the RR interval (heart-rate).

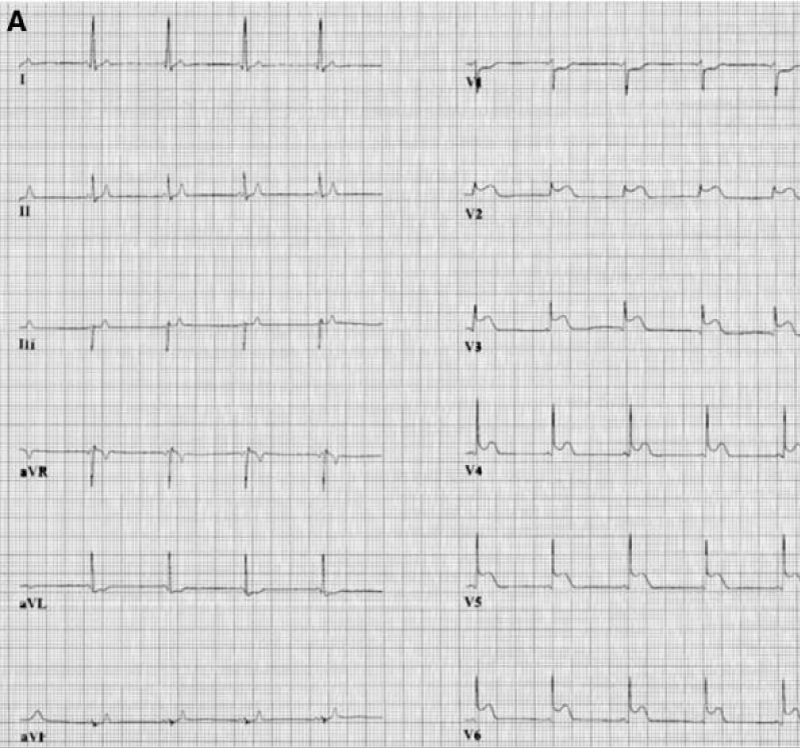

Figure 3: A typical association of the Breijo model and the Wellens pattern [7].

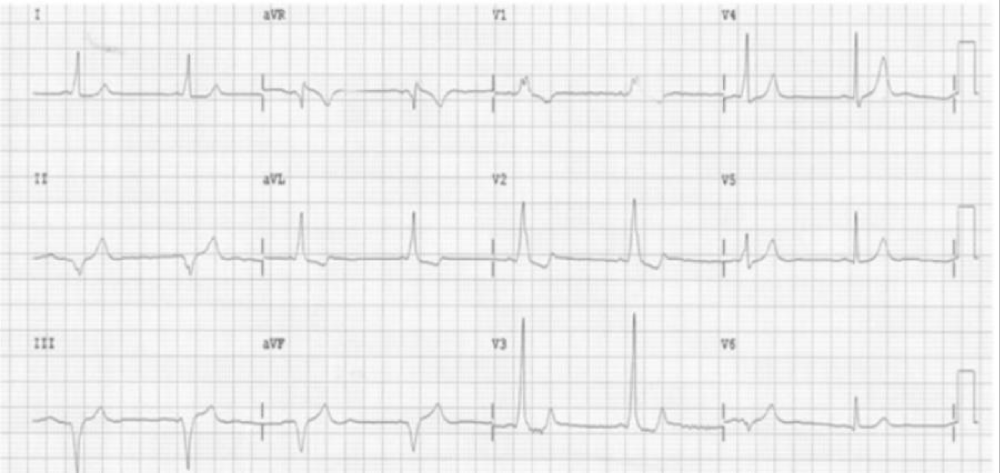

Figure 4: Values obtained utilizing the most commonly used formulas relating the measured value of the QT interval and the RR interval (heart-rate).

As a graphic example of this cardiac electrical abnormality, we can see the image of a basal ECG in a patient suffering from PR and QTc interval short below he PR interval is 0.100 milliseconds: Short. The QTc interval was evaluated according to the most commonly used formulas; in no case does it overcome 0.350 milliseconds.

- Breijo-Marquez FR. Decrease of electrical cardiac systole. Int J Cardiol. 2008; 126: e36–e38. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18374433

- Ward DE, Bexton R, Camm AJ. Characteristics of atrio-His conduction in the short PR interval, normal QRS complex syndrome. Evidence for enhanced slow-pathway conduction. Eur Heart J. 1983; 4: 882-888. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6662116

- Gollob MH, Redpath CJ, Roberts JD. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57: 802-812. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21310316

- Bjerregaard Preben, Gussak Ihor. Short QT Syndrome Electrical Diseases of the Heart 2013. Springer London. 569–578.

- Gussak I, Brugada P, Brugada J, Wright RS, Kopecky SL, et al. Idiopathic short QT interval: a new clinical syndrome?. Cardiology. 2000; 94: 99-102. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11173780

- Antzelevich Charles, Burashnikov Alexander. Mechanisms of Cardiac Arrhythmias. Electrical Diseases of the Heart 2013. Springer London. 93–128.

- Breijo-Márquez FR, Ríos MP, Baños MA. Presence of critical stenosis in left anterior descending coronary artery alongside a short "P-R" and "Q-T" pattern, in the same electrocardiographic record. J Electrocardiol. 2010; 43: 422-424. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20392452

- Breijo-Marquez FR. A Breijo Pattern Associated to a Wolff-Parkinson-White Pattern. J Cardiol Curr Res. 2016; 5: 00161.

- Breijo-Márquez FR. Sudden cardiac death in a young adult diagnosed with Tietze syndrome. Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2009; 17: 99-103.